Recollections of the Elwood Sailing Club

1943 to 1958

By Rod Dovey (2008)

CLIFF DOVEY 1913 – 1986

Dad was born in South Yarra and whilst still a young boy, his family purchased a weatherboard cottage at 83 Martin St. Gardenvale. This was his introduction to the seaside and he joined the North Road Life Saving Club. At that time there was a lawn, clubhouse and pier at the end of North Road. He competed in Life Saving carnivals, swam in the one and two mile Yarra swims and was keen on gymnastics. He once caused a bit of a fuss by doing a handstand several stories up, on the parapet of the YMCA, South Melbourne.

It was a pleasant sight to look across from the lawns of the life saving club towards Elwood beach and see the Seahorses lined up on the beach, or sailing to and from a mark, south of the end of the pier. It wasn’t long before he was tempted into sailing.

His first boat was E 14, L’Avenir. In this he was reasonably successful but felt he wanted something better.

His next boat was E 8, Aquila ll, and chosen because at that time it was the only Seahorse built by a professional boat builder.

With this boat he was very competitive and many were the duels with his archrival, Jim Pritchard in E 23, Huia. Together they shared the trophies for quite a few years.

Dad was inventive. Masts were mounted from the keel up through the deck and breakages were common, chiefly as a consequence of the shortage of wire and fittings at the closing stages of WWII and the early post-war years. Turnbuckles were scarce so cord line was used to secure the wire shrouds and the forestay to the deck fittings. A fierce gybe, – my father was renowned for running by-the-lee, – saw many a mast snap at the deck entry as the shroud or stay gave way. Dad got the idea of mounting the mast at deck level, supported from below by a thrust pole. Initially, he cast a hinged joint with a rod into the base of the mast and another into the thrust pole but later designed a shallow knob for the mast base and a spoon socket for the deck. Now, when they lost a mast overboard, it was just a matter of replacing the cord lines for the shroud or stay and not have to make a new mast.

The deck mounting didn’t save the mast on the occasion when we were returning from the ANA Day (now called Australia Day) regatta at Brighton and a southerly change hit us. Instead of throwing up into the wind and shortening or dropping the sails, Dad said “We’ll ride it home!” The four of us were hiking out when Spag, the for’ard hand shouted, “Jeez, look at the mast!” Remember that despite this being a sliding gunter rig, yet we could see that the short mast had an obvious S-bend in it. There was a bang and the next thing we knew, we were in the water, the boat several boat lengths ahead, still upright, the deck swept clean, – no rig, no crew, nothing. After we climbed back aboard and pulled in the remains there wasn’t a piece of the mast longer than three feet (1.0m) with each end shattered outwards. The mast had come down under compression!

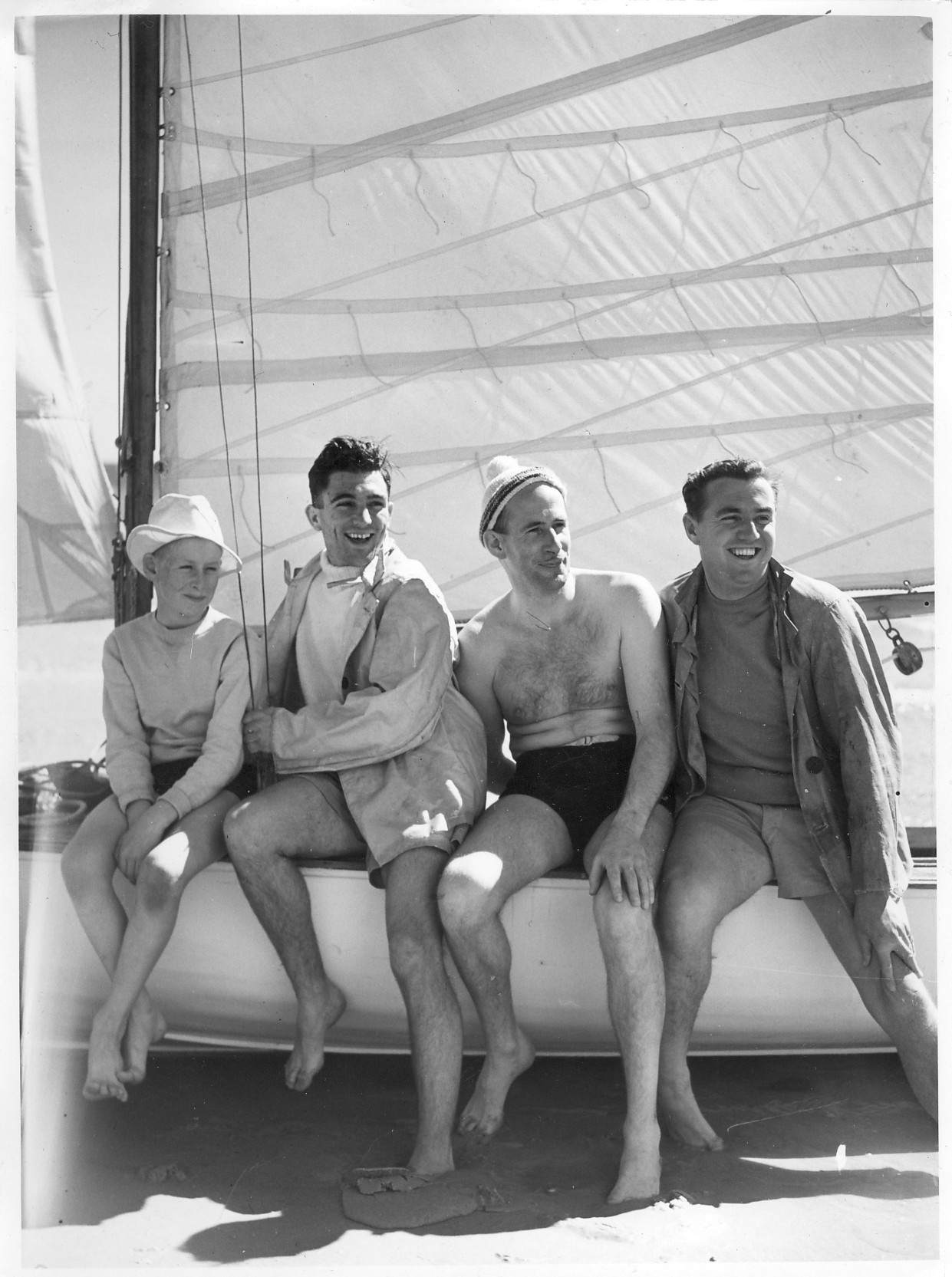

Crew of E 8, Aquila ll, circa mid 1940’s

Bail boy: Rod Dovey, For’ard: Spag ?, Skipper: Cliff Dovey, Main: Geoff Stahl

Another of Dad’s innovations, for which I as bail boy was to reap a dubious benefit, was the platecase-mounted pump. Bail boys were necessary as Seahorses shipped a lot of water going to windward on rough days. I would toil away down to leeward on the up-wind legs, with a canvas bucket which had a wire strop holding open the mouth, scooping up the water on the lee roll, casting it over the side and then back for the next load. The only respite came on the downwind leg provided I had cleared most of the water from the cockpit. Then Dad designed and made these pumps, one each side of the platecase. Rectangular in cross–section they each had a brass garden tap handle and a greenhide leather thong. You stood over the pumps working the handles firstly with your arms, then your back and finally your knees! If your weight was needed up on the side then you had to keep pumping with the leather thongs. Years later I thought what a pity he didn’t think to drill a hole in the bottom of the cockpit and drop in a Venturi!

Bail boys were able to be at the club early on Saturdays. Most men worked on Saturday mornings so we tried to get the boats down to the waters edge to give them an early start. (Also, to curry favour with the skipper, because if the weather was light we really wouldn’t be needed for the race!) We would wheel the boats on their trolleys down to the foreshore then, provided we could round up sufficient able bodies lift them off the trolley to the sand, bow to the wind. Most times we weren’t strong enough to put up the mast, but we would assemble everything beside the boat ready for the crew’s arrival.

Getting the boats rigged.

(Note the starting clock and the small 2nd storey area of the clubhouse)

About 1943 or 44, travel on trains and coaches was very restricted; cars and petrol were both scarce, so for a holiday Mum, Dad and I took off in the Seahorse to “cruise the Bay.” Dad had scrounged a quantity of lead, which he was able to cast into two bricks to fit the keelson and ribs of the cockpit floor. This gave us added stability – not enough to totally prevent a capsize, – but enough to make it unlikely. Several years later, the club made a ‘cruising plate’ that had a lead bulb at it’s bottom and necessitated anchoring in shallow water overnight rather than beaching.

Leaving from Elwood, we sailed across to Point Cook and made camp on the beach. Our evening meal was cooked over a driftwood fire and I remember that it was my first taste of fried onions, which at home I had always eschewed, but in this outdoor setting, after a long day’s sail, the tempting odour was irresistible. We slept in army disposal, kapok filled sleeping bags, digging a hip hole in the sand and having a canvas tarpaulin on hand sufficient to cover the three of us, in case of rain. Next morning we were awoken with the roar of a plane overhead; we were camped at the end of the airstrip! These planes, – I think they were Hudson’s, – were the dawn coastal patrol looking for enemy submarines or shipping which might be lurking off Port Phillip Heads. Later, as we set sail, another plane took off. Like all small boys in wartime, I was gun aware so I made two guns with the fingers and thumbs of each hand, aimed at the aircraft and made the appropriate noises, “ Ack, ack, ack.” The tail gunner must have had a sense of humour or else he was just clearing his guns, for he let go a burst into the water about 100m behind the Seahorse! I thought I’d started another war! We sailed up to Little River hoping to buy food at the local store, only to find it closed. We asked a local sitting outside what time the store closed. He replied “About 5 o’clock.” This was perplexing; we thought that right then it was about lunchtime although we didn’t have a watch. “What time is it?” we asked. “About ten to eight” was the reply. We must have been up very, very early!

We crossed Corio Bay to Clifton Springs and set up camp for a few days in Buckley’s Cave. Many years later I returned for a look and found the cave protected by a steel grill, but at that time it was open to all and sundry. I remember that there was a shelf carved into the back wall. Several days later we sailed on to Portarlington, encountering very strong winds as we rounded Point Richards. Dad and Mum were hiking and working the sheets like mad to keep us upright and I was flat chat on the pumps. Even though it was then just a short beat into Portarlington, by the time we arrived we were exhausted and our temper was not helped when bystanders did just that; – stood by as we strained to drag the boat up onto the sand. A local fisherman saw our problem and came and gave us a hand then invited us back to his place for a shower and a cup of tea. Onwards, our last stop was Chelsea; where we slept on the beach outside the sailing club, then home to Elwood.

Lady Skippers Race

An earlier memory of the wartime was when we sailed up to Port Melbourne to gawk at a U.S. aircraft carrier berthed at Station or Princes Pier. As we closed in towards it, a very American voice boomed from a tannoy across the water,

“E 14! E 14! This is a restricted area! This is a restricted area, keep clear!”

To reinforce the sentiments he was expressing, every gun on our side of the carrier spun to aim directly at us! We left!

At that time, 1943 – 45, the only men around were those unfit for active service or, as in the case of my father and most of the other members, those in the essential industries. The club itself, although large in it’s footprint, only had a floor in the front half. I remember the back half being concreted about the early fifties. Upstairs was an attic-like committee room to the left of the staircase, then on the right an open area for the starter who had number boards and a handle to turn the hand on the large clock dial on the front of the clubhouse. A table tennis table just managed to fit here as well. Finally, at the other end was a narrow passage with lockers on each side. After each days sail, crews would cram into this area, shedding oilskins, joking with one another, joshing other crews about tactics, rights of way, etc.

If you wanted to sail, the only way in those days was to join a club. This was because boats were heavy and had to be stored near the beach, which was the same reason for the existence of the Angling Club, next-door. It wasn’t until the introduction and availability of plywood, and the general adoption of the automobile, that things changed. I distinctly remember the first time that a car pulled up in the car park, unloaded a dinghy from a trailer, carried it down to the beach and proceeded to rig and sail it. We were absolutely dumbfounded! Who’s this? What club do they come from? Why hadn’t they made themselves known to us before sailing off our beach? Sailing changed from that moment. Up until then anyone on the water was responsible to a club who made sure that they were competent and observed the protocols and safety measures. When Tony Jacobs first bought his Seahorse the committee told him that he would have to sail as crew until he was more proficient at helming. Before the start of each season each Seahorse was “bottle” tested to ensure that hatches were watertight. That’s what a club could do. But now, anyone could launch a boat and get into all sorts of strife. So started the government bureaucracy of rules and regulations that blights our sport to this day.

E 5, Hirondelle

ES PRIOR

Es (mond) Prior and my father were great friends. Es was the club Secretary at the time, later to be the Commodore. He was a sailmaker with his loft at the rear of his house in Ripponlea. His Seahorse was E5, Hirondelle (Fr. n. swallow) which was different to others in that it had a pointier bow and measured 18 foot 6 inches overall against the Seahorse standard of 18 foot.

Es lived and breathed Seahorses, the Elwood Sailing Club and his dog, Gyp. Much to everyone’s surprise, about 1956 or 57, Es, who we all thought was a bachelor for life, met and married Olive. The wedding was timed for late on a Saturday, after the racing was over. Seahorses took considerable maintenance; after each sail they had to be washed with fresh water and scrupulously dried in every nook and cranny between ribs and stringers and inside the hatches. Sails and spars had to be hung to dry.

“Off you go, Es,” we all said.

“It’s your wedding day, we’ll look after the boat.”

After a short demurring, Es left. As we were all invited to the wedding, we knuckled down to the work of putting the boats away when, 15 minutes later, Es is back!

“What the hell are you doing here,” we exclaimed.

“Oh, I’ve got to take Gyp for his walk!” Es replied.

Needless to say, Gyp went on the honeymoon and slept where he always slept, on the bed beside Es. Ask Olive!

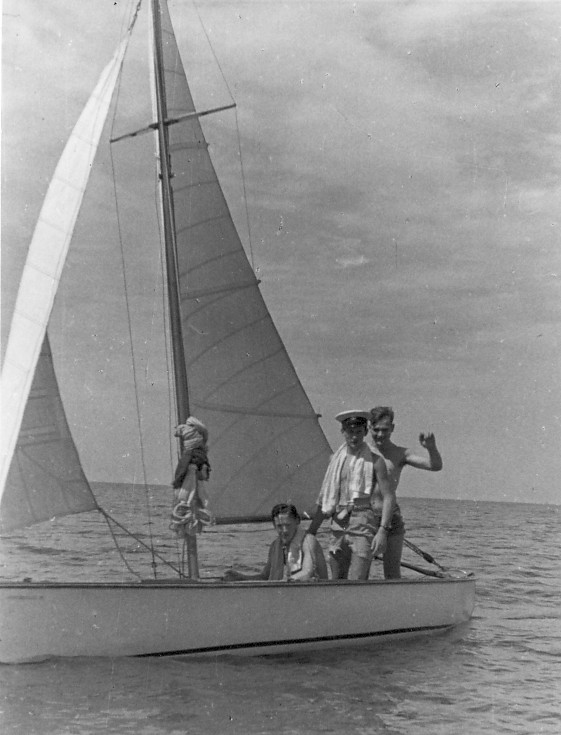

Tumlaren, Zonga with mast intact

Before the war ended, Dad and Es managed to borrow from a Navy Commander, the Tumlaren Zonga, for a “round the Bay” cruise. Everything went well until we got to Sorrento when the main halyard jumped off the sheave at the top of the mast and was jammed in the slot. As I was only a little fellow, they tried hoisting me up but I got frightened before I’d even reached the spreaders. They decided to wait for low tide and pull the mast over towards the pier using another halyard. Es watched the angles from the dinghy, my mother and Es’ partner eased out the bow and stern lines and Dad had charge of the halyard. He was struggling, – it’s not as easy as you might think to get a boat to lay over this way. Calling for some help, some passing soldiers joined him and lustily singing “A Life On The Ocean Wave,” proceeded to really put in some grunt. Nobody heard Es’ cry, “Stop! Stop!” With a sharp crack the mast split!

The broken mast

Es Prior and his spliced mast

What do we do now? Tum’s don’t have an engine and the Commander wants his boat for his own cruise, the week after next. In a remarkable example of seamanship, Es sheer-lashed the two bits of mast together, shortened shrouds and stays and under trysail and storm jib we brought the boat back to its mooring at what was then called the Royal St Kilda Yacht Club, now the Royal Melbourne Yacht Squadron. Over the next week, Dad and Es made a new Tumlaren mast on the workbench that ran along the inside back wall of the ESC clubhouse, stepping it just in time for the Commander’s return.

Not long after the war ended, a couple of enterprising ex-servicemen bought three ridge tents and three Snipe class yachts and set up a camp in Newland Arm, near Paynesville on the Gippsland Lakes (photo:Cliff & Rod Dovey in a Snipe). They sent leaflets to all the yacht clubs, inviting members to hire a tent and yacht for a sailing holiday. Dad, Mum and I took one tent, Es and I think, his girlfriend at the time, Mary Finlayson and, I think, Jo Johansson took another. The Morris family of Morris Dairies fame took the third tent. They brought with them, what was to us, a very unusual boat. A scow hull about 12 foot long, no cockpit, cat-rigged, but horror upon horror, it was painted bright orange! In those days we all believed that any self-respecting yacht should have a white hull and varnished deck and interior. Mr Morris told us that he’d built it from a plan in Popular Mechanics and it was called a Moth. This was the first Moth in Australia and the class went on to be one of the most popular in the world.

Not long after the war ended, a couple of enterprising ex-servicemen bought three ridge tents and three Snipe class yachts and set up a camp in Newland Arm, near Paynesville on the Gippsland Lakes (photo:Cliff & Rod Dovey in a Snipe). They sent leaflets to all the yacht clubs, inviting members to hire a tent and yacht for a sailing holiday. Dad, Mum and I took one tent, Es and I think, his girlfriend at the time, Mary Finlayson and, I think, Jo Johansson took another. The Morris family of Morris Dairies fame took the third tent. They brought with them, what was to us, a very unusual boat. A scow hull about 12 foot long, no cockpit, cat-rigged, but horror upon horror, it was painted bright orange! In those days we all believed that any self-respecting yacht should have a white hull and varnished deck and interior. Mr Morris told us that he’d built it from a plan in Popular Mechanics and it was called a Moth. This was the first Moth in Australia and the class went on to be one of the most popular in the world.

1956 OLYMPICS

There had long been a rivalry between the Elwood Seahorses and the Black Rock Sharpies, (12sq metres). Both carried a similar area of sail on the same sliding gunter (gaff) rig. The Sharpie was hard chined and beamier than the Seahorse with it’s canoe hull and narrow beam. So it was with some chagrin that the Sharpie was chosen for the 1956 Olympics, but understandable as it was an International class. Elwood got it’s own back by being chosen as the host club for this Olympic event and Es Prior decided that the club should have an entry in the Australian selection trials. For reasons that I am not aware, some of the selection races were sailed two-up, some three-up. In the latter case, I sailed as main-hand with Es and his for’ard hand, Jo Johansson. Victoria had the largest fleet of Sharpies so it was reasonable to think that one of the local boats would win the trials. It was not to be. This young pup from Western Australia beat the pants off us; some feller called Rolly Tasker!

The ESC entry in the 1956, 12 sq metre Olympic trials

The ESC entry in the 1956, 12 sq metre Olympic trials

For’ard: Jo Johannson, Main: Rod Dovey, Skipper: Es Prior

Initially, the international fleet congregated at Elwood but after so many got into strife trying to get through the surf in strong southerlies, – some ended up smashing into the Angling Club’s ramp, – they were offered the opportunity to relocate across to Hobson’s Bay. All but two took up the offer, the exceptions being the Australian boat and the USSR boat; the latter thinking it best to stick with the locals. Little did they know that the “locals” came from over 2000km away! The USSR team were great blokes who sailed on the Black Sea. Their boat didn’t meet specifications regarding the tiller so ESC member, Harold Cooper who lived just up the road in

Pine Av. took them home and together they crafted an approved tiller. This all had to be done when the KGB minders were absent. 1956 was the height of the Cold War and the Russians were paranoid that their team members might abscond.

Unfortunately for them, they had assumed that all the yachting would be held from one venue and had allocated just one pair of KGB agents to watch their teams. It had to be a pair because they had to watch each other as well! Every day the bus would leave the Olympic village with the USSR yachting team and travel around the Bay, from Williamstown past St Kilda, Elwood, Brighton and onto Sandringham, dropping off crews as it went. The two KGB guys could only pick one venue for that day. If it happened to be Elwood, the two Russian Sharpie guys wouldn’t recognise you. They would pretend to not understand your query and tried as much as possible to keep to themselves, with a rare, warning turn of the eye and a flick of the head in the direction of the KGB goons. On the other hand, when the KGB weren’t around, these same sailors were wonderful, cheerful companions, anxious to learn as much as they could about our lifestyles. I recall that they were amazed that at age 21, I had a car, albeit a 1927 A-Model Ford!

The Olympic flag flies outside the Elwood Sailing Club

The Olympic flag flies outside the Elwood Sailing Club

My memory is hazy regarding the battle for the Gold. There were some strong winds during the races and on the last race I think Tasker only had to finish midway in the field to take the Gold. For safety sake he sailed the last lap on jib alone, – I think he was still first over the line, – but the Indian (?) crew protested him for a “before the start” infringement, which was cruelly upheld, relegating Australia to the Bronze.

Falcon comes in from the last race

Australia’s Rolly Tasker wins Bronze

THE ESC SONGBOOK

Some of the songs composed by Seahorse sailors whilst under the influence of dubious concoctions of alcoholic liquors.

THE SEAHORSE SONG

I’m a yachtsman, I’m a yachtsman, I sail the high seas,

Come bottle with me and we’ll all do a freeze.

In my Seahorse, in my Seahorse, I’ll show you some tricks,

We’ll bust all the battens and smash all the sticks.

We’ll gybe and we’ll lee’oh, we’ll blow out the jib,

We’ll tear off the canvas ad nauseam, – (ad lib).

We’ll fill up the cockpit with dirty green seas,

We’ll sail the ship under ‘till Hell it does freeze.

In jumpers and slickers, we’re muffed to the throat,

‘till some silly b——- just bottles the boat.

So come ye to Elwood and be one of us,

A splay footed, bald headed, lousy old cuss!

THE ELWOOD SONG

(To the tune of the Marines Hymn)

From the shores of stormy Elwood, we will put our boats to sea.

We will sail them north and southwards, just as far as the eye can see.

For we’re old sea dogs that sail them, we’re as tough as tough can be,

As we stand on the club veranda, gazing wide-eyed out to sea.

For we’re waiting for the day to dawn, when the seas will be quite flat,

Then we’ll don our worn out slickers and old-time sailing hats!

SOME PERSONALITIES SONG

Little Willy Owens is a man who owns a boat,

And every time he puts it in, he hopes that it will float,

And when the wind is blowing and Willy yells out “gybe,”

You’ll find our Yankee upside down with the crew out on the side.

Then we come to Cliff Dovey, as tough as tough can be,

He can’t keep Aquila upright when running by-the-lee,

And when the boat does bottle, if you happen to be near,

You’d think he was a refugee from the language you can hear.

Then there’s our Secretary Prior who owns sweet Hirondelle,

The boys all call him Omar Khayyam, ‘cos he makes tents so well.

(And the rest, like so much else, is forgotten)

SOME FINAL THOUGHTS

Each Easter, many of the Seahorse fleet would head for Frankston. Beer in large bottles, – there were no stubbies or cans, – would be loaded into the hatches together with food and bedding. Arriving at Frankston on Good Friday, we would join the crowd from clubs from all around the Bay. At that time the beach was lined with tea-tree shelters and we would commandeer two or three for the Elwood Sailing Club.

One year, one of our members who I can only remember as ‘Smithy,” slung a hammock beneath the shelter. Smithy was a wild bastard. He once took me for a ride on his motorbike and while we were hurtling along Beaconsfield Parade, he stood, turned around and sat down facing me! He also liked his grog. This night at Frankston he passed out in his hammock so some of the boys decided to have a bit of fun. They quietly tied him securely in the hammock, unhooked the ends and carefully carried him towards the creek. There was a footbridge across the creek that opened to let the masted fishing boats in and out. You wound a handle, the bridge split in the middle and each side lifted up like a smaller version of the Tower Bridge across the Thames. As they opened the bridge they attached the hammock to each side, then retired. At dawn the next day, the whole beachfront and half of Frankston was awakened by the hoots of fishing boats and the screams of Smithy who could do nothing about his predicament.

As well as the pier at North Road there was also a pier at Point Ormond. This lost a few spans in its middle during a gale. I once beat Chris Wilson in a race in our Sabots from St Kilda to Elwood by sailing through the gap in the pier. To celebrate the lights being turned on in Melbourne at the end of the war, the army fired a display of pyrotechnics including star shells, from Point Ormond using artillery. The next day, us kids swam out and retrieved the little parachutes. There was a kiosk at the back of the point and a single bogie tram, called a toast rack, used to run from Elsternwick railway station to bring summer picnickers down to the seaside. On weekends a bloke ran pony rides between the point and the start of Elwood beach.

In 1952, I was on study vac. before sitting for my Matriculation, now called HSC. It was a hot day, so for a break from the books I headed down to the club. Somehow I was coerced into joining the crew of one of three boats who, despite my protestations, proceeded to sail across to Point Cook! By the time that we turned for the return trip both the wind and the light were fading fast. Two boats including the one that I was on, headed on a course straight for Elwood whilst the third decided to follow the shoreline past Altona and Williamstown. They chose wisely; they picked up a lovely sea breeze that held, 100m offshore, whilst we wallowed out in the middle of the Bay with nothing. I can still see the silhouette of our companion Seahorse in the lights of a steamer that nearly ran it down. We got back about a few minutes before midnight to be greeted by my father who had been furiously pacing the shore since nightfall.

By 1958, I was married, a father of the first of four children and concentrating on establishing my career. When we relocated away from Elwood, my sailing became very intermittent and was not fully revived until 1987 when I took a year off work and my wife and I cruised the East Coast. Then I started doing yacht deliveries – but that’s another story.

Yes Graham did win a quickcat nationals at elwood, by the way max press i think was from parkdale.there was am incident in the last race between 3 boats myself, ray cromb and max press at the finish i had won the regatta and was at elwood theatre putting up decorations for the presentation nite when called back to the club for a protest lodged by max press against ray cromb. our committee in their wisdom disqualified me and graham became the champ. to the best of my recollections.

regards to all at esc